Ursula K. Le Guin left us with a wealth of stories and universes, but my favorite might be her Hainish cycle. I recently read, or re-read, every single novel and short story in the Hainish universe from beginning to end, and the whole of this story-cycle turned out to be much more meaningful than its separate parts.

Some vague and/or minor spoilers ahead…

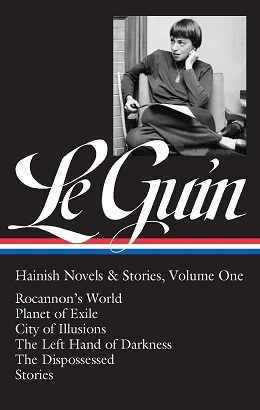

The Hainish Cycle spans decades of Le Guin’s career, starting with Rocannon’s World (1966) and ending with The Telling (2000). In between are award-winning masterworks like The Left Hand of Darkness, The Dispossessed, The Word for World is Forest, and Four Ways to Forgiveness. And the Library of America has put out a gorgeous two-volume set collecting every single piece of narrative Le Guin published involving Hain and the Ekumen. As with her other famous setting, Earthsea, this is a world to which Le Guin returned in the 1990s after a long hiatus, and it’s a much richer and more complex world in the later tales.

(And it’s also very clear, that as Le Guin herself has admitted, there is zero continuity between these books and stories. Anyone who tried to assemble a coherent timeline of the Ekumen or Hain might as well give up and go try to explain how all the X-Men movies take place in the same universe, instead.)

In the three early novels (Rocannon’s World, Planet of Exile, and City of Illusions), Le Guin’s star-spanning advanced society isn’t even called the Ekumen—instead, it’s the League of All Worlds, and it’s at war with some mysterious enemy that’s equally advanced. (We only really glimpse this enemy when we meet the nefarious Shing in City of Illusions, who have taken over a post-apocalyptic Earth and are somehow involved in the war against the League.

At first, the League or Ekumen simply appears as a backdrop, barely glimpsed off in the distance, which sends an advanced observer to a more primitive planet. In one of the later stories, Le Guin has someone remark that Ekumen observers “often go native” on primitive worlds, and this is a huge concern in the early Hainish novels.

Rocannon, the hero of Rocannon’s World, is alone on a planet of barbarians and flying cats, and he wears a full-body protective garment called an Impermasuit that literally protects him from touching anyone or being too affected by his surroundings. Meanwhile, Jakob Agat, the hero of Planet of Exile, hooks up with a young native girl, Rolery, whom his comrades view as a primitive native, and the question of whether they can really interbreed becomes crucial to the novel’s story. In City of Illusions, Falk actually has gone native, until something too spoilery to reveal happens.

When you read those three novels right before The Left Hand of Darkness, the story of Genly Ai alone among the mostly genderless Gethenians (whom he fails spectacularly to understand) takes on a different feel. Where previously I always saw Genly as the ultimate outsider, visiting a world where his gender and sexuality are alien to everyone else, I now saw him as just another in a long line of advanced visitors who are struggling against the temptation of assimilation with less-advanced people.

Another recurring concern becomes very apparent when you read all of the Hainish stories together: modernity, and its discontents. The barbarians in Planet of Exile are under threat by a northern group called the Gaal, which had previously wandered south for the winter in disorganized, relatively harmless groups. But now a new leader has organized the Gaal into one nation—much like the King-Beyond-the-Wall Mance Rayder in George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire—and they’re marching south as an organized army. This is a world that has never known armies, or nation-states, and nobody except the handful of alien visitors knows what to do about it. (And it’s hinted the Gaal may have gotten the idea, in part, from watching the alien exiles from the League of Worlds.)

Similarly, in The Left Hand of Darkness, the planet Gethen has never had a war, and though it has nations, the modern nation-state is a relatively new innovation. Orgoreyn is marching into a future of patriotism and becoming a state with territorial ambitions, and in their neighboring country, Karhide, only Estraven is astute enough to see where this is going to lead. And then, in The Telling, the planet of Aka has become a modern nation-state almost overnight, under the rule of a blandly sinister Corporation, and this is explicitly the fault of some Terrans who came and meddled.

The worldbuilding in these books also becomes much more complex and layered starting with Left Hand of Darkness. Where we get hints and glimpses of strange customs and odd worldviews in the first three books, like the natives in Planet of Exile having a taboo on making eye contact, we suddenly get a much fuller understanding of the fabrics of the societies Le Guin creates. And I found my reading slowing down, because almost every paragraph contained some nugget of wisdom or some beautifully observed emotional moment that I had to pause and appreciate more fully. The first few books are corking adventures, but everything after that is a mind-expanding journey.

Buy the Book

The City in the Middle of the Night

Another interesting thing: the famously intense winter crossing that Genly and Estraven take in The Left Hand of Darkness also shows up in Rocannon’s World and Planet of Exile, though in neither book is it as well-drawn or epic. (And of course, Rocannon has his Impermasuit to keep him from getting too chilly.) There’s also another long slog through a frozen landscape in The Telling, but it’s much gentler and more well-planned, as if Le Guin finally decided to allow her characters to enjoy a winter trek instead of suffering through one.

And notably, there are few women in the earlier stories, and the ones that do show up are hard done by. (This time around, I found myself wishing more than ever that we’d gotten to see more of Takver and her journey in The Dispossessed.)

Le Guin changed her mind about some aspects of the Hainish universe as she went. For example, in the early novels, including Left Hand, some people have a telepathic ability known as Mindspeech, but following Left Hand, she decided to get rid of it, and it’s never mentioned again. (Mindspeech would have come in very handy in Five Ways to Forgiveness and The Telling.) Also, it’s a major plot point in the early novels that uncrewed ships can travel at faster-than-light speeds, but crewed ones cannot…so people are able to fire missiles from across the galaxy and have them hit their targets almost instantly. This stops being true sometime in the mid-1970s.

But more importantly, the Ekumen stops being quite so hands-off. In the early Hainish novels, Le Guin makes much of the Law of Cultural Embargo, which is basically the same as Star Trek‘s Prime Directive. (Except she got there first.) The travelers who visit primitive worlds are very careful to avoid sharing too much technology, or even much knowledge of the rest of the universe. But by the time The Telling rolls around, we’re told that the Ekumen has an explicit rule, or ethos, that its people will share information with anyone who wants it.

It’s no coincidence that the Ekumen becomes much more explicitly a force for good, and an interventionist one at that. We first see the Ekumen making a real difference in The Word for World is Forest, where its representatives show up and basically make the Terrans stop exploiting the native “Creechers” on the planet Athshe as slave labor. (And the Ansible, which we see Shevek invent in The Dispossessed, makes a huge difference. The Terran colonizers haven’t been able to communicate in real time with home, until they’re given an Ansible.)

And then, in Five Ways and The Telling, the Ekumen’s representatives are suddenly willing to make all kinds of trouble. In Five Ways, the ambassador known as Old Music helps slaves escape from the oppressive planet Werel to the neighboring Yeowe, where slaves have led a successful uprising. And in one story included in Forgiveness, “A Man of the People,” Havzhiva uses his influence in various subtle (and not-so-subtle) ways to push the ex-slaves on Yeowe to abandon their patriarchal mindset and grant women equal rights. In The Telling, Sutty and her boss, Tong Ov, conspire quietly to preserve the native culture of Aka, which is in danger of being destroyed altogether by the Terran-influenced ruling Corporation.

I mentioned that humans can’t travel faster than light in these stories…except that in a cluster of stories that were mostly collected in the book A Fisherman of the Inland Sea, there’s an experimental technology called Churtening. It’s more or less the same as “tessering” in A Wrinkle in Time, except that there’s a spiritual dimension to it, and you can’t really Churten unless your entire group is in harmony with each other. And when you arrive instantaneously at your far-off destination, reality is liable to be a bit wobbly and unmoored, and different people may experience the visit very differently.

The Left Hand of Darkness is Le Guin’s most famous experiment with destabilizing gender: a whole world of people who are gender-neutral most of the time, except when they go into “kemmer,” a kind of estrus in which they become either male or female for a while. But in these later stories, there are more gender experiments, which are just as provocative and perhaps more subtle. In “The Matter of Seggri,” there’s a world where women massively outnumber men, who are kept locked up in castles and forced to compete for the honor of serving in brothels where the women pay them for sex.

Likewise, there’s “Solitude,” which takes place on a planet where women live alone but together, in communities called Auntrings, and the men live outside the community, though some “settled men” also live together—and as on Seggri, the women initiate sex. And “In a Fisherman of the Inland Sea,” there’s the four-way marital institution of Sedoteru, in which a couple of Morning people marries a couple of Evening people, and homosexuality is strongly encouraged—but love among two Morning people or two Evening people is a huge taboo.

Another interesting motif in these books is unresolved sexual tension; plus sexual agency, and who has it, and why it matters. In the early books, Le Guin matter-of-factly has teenage girls shacking up with much older men, and nobody seems to find this unusual. But then in Left Hand of Darkness, there are multiple situations where choosing not to give in to sexual temptation is clearly the right (but difficult) choice. Estraven is tempted while in kemmer, first by a sleazy government operative in Orgoreyn, and then by Genly Ai. And Genly, meanwhile, gets trapped with another person in kemmer. (And when you read the short story “Coming of Age in Karhide,” the intensity of desire in kemmer, and the danger of giving in to the wrong person, is underscored.)

Then in the later stories, we find out that people from Hain can control their fertility, and this gives them a whole other layer of sexual agency that nobody possessed in the earlier books. In “Seggri” and “Solitude,” as mentioned earlier, women have all the sexual power. In “A Fisherman of the Inland Sea,” Le Guin finds the one way to write a forbidden sexual attraction in her society. It takes until Five Ways to Forgiveness that Le Guin actually starts writing straight-up romances, which follow the normal trajectory of most romance novels, in which people learn to understand each other and form romantic and sexual partnerships based on respect—and it’s delightful, even against this horrendous backdrop of slavery and exploitation.

Buy the Book

Ursula K. Le Guin: Hainish Novels & Stories, Volume One

Later Le Guin is also much dirtier and queerer than earlier Le Guin—and more frank when discussing sexuality compared with all those offhand references to “coupling” in The Dispossessed. Also, her older women characters are suddenly allowed to have a healthy sexuality (and even to hook up with much younger partners, though not actual teenagers this time.)

Two of my favorite moments in these stories come when someone holds a baby. In The Dispossessed, Bedap holds Shevek and Takver’s newborn child and suddenly has an epiphany about why people can be cruel to vulnerable people—but also, conversely, about the nature of parental feelings (like protectiveness). And then in “Old Music and the Slave Women,” Old Music holds a child born to slaves, who is slowly dying of a totally curable disease, and there’s so much tenderness and rage and wonder and sadness in that moment.

The Word for World is Forest is the first time we start to get a glimpse of the Ekumen as a functioning society, rather than just someplace that people come from. But starting in the 1990s, Le Guin really starts to develop the Ekumen as a mixing of cultures: a bustling, noisy, vibrant society. We actually get to visit Hain, the place where all of humanity, all over the galaxy, came from originally. And all of a sudden, the Gethenians from Left Hand of Darkness and the Annaresti from The Dispossessed are just hanging out with everyone else (though I’m not sure if it’s explained how the Gethenians deal with going into kemmer, so far from home.)

The Ekumen has its own political divisions and debates, as it tries to figure out how to engage with the slave-owning culture of Werel, an Earth overrun by religious fundamentalists, and the corporate dystopia of Aka. And even though the Ekumen always seems wiser and more patient than other societies, its representatives are allowed to have differences of opinion, and to argue among themselves and make things up as they go along.

The Telling feels like a fitting climax to the Hainish cycle, in many ways. The running themes of spirituality and community get their fullest explanation in this book, where a Terran named Sutty strives to explore a quasi-monastic storytelling culture that is in danger of extinction. In City of Exile, just reading the opening lines of the Dao De Jing has miraculous mind-rescuing powers, and Genly and Estraven discuss the yin/yang symbol, but the Eastern-influenced spirituality feels both subtler and richer in The Telling. Moreover, Le Guin’s interstellar society feels fully to have come into its own, both as a polity and as a force for good.

I haven’t said as much about The Dispossessed, partly because it feels very different than all the other Hainish stories, with its story of a physicist from a world of anarchists visiting a capitalist planet. The Ekumen feels less like a crucial presence in The Dispossessed than in all the other stories—but The Dispossessed remains my favorite Le Guin novel, and I continue to get more out of it every time I re-read it.

When read and considered as a whole, Le Guin’s Hainish Cycle feels like an even more impressive accomplishment than its stellar individual works. Not because of any internal consistency, or an over-arching storyline—you’ll have to look elsewhere for those things—but because of how far she takes the notion of an alliance of worlds interacting with baffling, layered, deeply complex cultures and trying to forge further connections with them. I’m barely scratching the surface here when it comes to all the wealth that’s contained in these books, gathered together.

These individual journeys will leave you different than you were before you embarked on them, and fully immersing yourself in the overarching journey might just leave you feeling like the Ekumen is a real entity—one to which we would all desperately like to apply for membership right about now.

Originally published February 2019.

Charlie Jane Anders’ latest novel is The City in the Middle of the Night. She’s also the author of All the Birds in the Sky, which won the Nebula, Crawford and Locus awards, and Choir Boy, which won a Lambda Literary Award. Plus a novella called Rock Manning Goes For Broke and a short story collection called Six Months, Three Days, Five Others. Her short fiction has appeared in Tor.com, Boston Review, Tin House, Conjunctions, The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, Wired magazine, Slate, Asimov’s Science Fiction, Lightspeed,ZYZZYVA, Catamaran Literary Review, McSweeney’s Internet Tendency and tons of anthologies. Her story “Six Months, Three Days” won a Hugo Award, and her story “Don’t Press Charges And I Won’t Sue” won a Theodore Sturgeon Award. Charlie Jane also organizes the monthly Writers With Drinks reading series, and co-hosts the podcast Our Opinions Are Correct with Annalee Newitz.

Hey Charlie,

Great essay! I really enjoyed watching you unravel all of Le Guin’s intricate stitching. I haven’t read all of the Hainish cycle, but you’ve inspired me to pick it up again.

The overarching theme you articulate toward the end—connections forged across the seemingly insurmountable gulfs between her planets’ cultures—does seem to be her favorite common thread. Personally, the cultural disparities and even incompatibilities that would be inherent in any interplanetary commingling has always fascinated me, even more so than Le Guin’s characters’ (or the Ekumen’s) efforts to bridge it. And I was really struck by the different ways in which she uses language in The Word for World is Forest to convey that gulf. Whereas Genly Ai helpfully explains the mysteries he encounters, Selver is simply baffled by the Terrans’ ways. The way in which Le Guin conveys his culture (even through Selver’s benumbed voice during a time of war) is such skillful storytelling. The difference between the villainous Terrans’ gruff (and annoyingly one-note) soldier-speak and the Athsheans’ half-understandable dream language kept me reading a book that some have criticized as being a polemic. It is that, but a great one, in part because of how fully she inhabits the Athsheans’ opposite worldview (which does echo that of our planet’s hunter-gatherer societies, but also emerges as its own believably alien culture, thanks largely to Le Guin’s dreamy language).

This is excellent. Thank you. I really need to read the 3 earliest novels. I’ve been hesitant to pick them up as I’ve heard that LHoD is just such a major leap, and I don’t want to tarnish my feelings for Le Guin. I picked up Lavinia (though I got dragged away) earlier this year, and was absolutely in awe of the prose.

An interesting tidbir about Left Hand: subtler than the overt mention of the ying-yang, the word “shadow” appears more than 50 times. I had a hunch about this, and did a quick search to confirm it an electronic copy of the text. I think Le Guin is toying with connections between the yin-yang and Jungian psychology.

Always loved these stories. What a writer! One aspect of this universe which a certain TV franchise should have taken a cue from is her explanation for why all these alien races are symmetrical two eyed two eared bipeds roughly 1.8 meters tall – they’re all the product of the Hains seeding worlds with variants of their genetic blueprint tens of millennia ago. ST TNG actually had an ep that threw this idea into the mix – but the seeding was done billions of years ago, which, given the way genes can drift, wouldn’t yield the same results at all.

@3/Lucy Rietmann: The problem with her explanation is that we have a pretty good fossil record leading up to us. This was even acknowledged in The Left Hand of Darkness, chapter 7: “But now that there is evidence to indicate that the Terran colony was an experiment, the planting of one Hainish Normal group on a world with its own proto-hominid autochthones […]” Which solves this problem but reintroduces the unlikely concept of parallel evolution, albeit only for two groups of hominids.

The TNG idea was actually pretty smart. The first hominids in it didn’t just seed alien planets with their genetic blueprint. They seeded a code that “directed your evolution toward a physical form resembling ours”, as the alien message explains to the characters in the episode. That’s the best explanation for the abundance of hominids in science fiction I’ve seen so far, and since the people who did the seeding are long gone, it also allowed Star Trek to do without a guiding elder race.

On a different note, I love Le Guin’s Hainish cycle, and it made me quite happy to read this article.

@3 — Not all the related species are 1.8 meters, of course — the Athsheans (from “The Word for World is Forest”) are much shorter. (Nitpick, yes.)

(My other nitpick is that I’d push the start of her “League of Worlds”/Ekumen stories to “Dowry of the Angyar” aka “Semley’s Necklace”, later the prologue to Rocannon’s World, which appeared in 1964. Which I mention just because short stories are important to me, and so are Cele Goldsmith Lalli’s magazines!)

Great essay — I read it back in February, of course, and happy to see it reprinted!

Old Music does explicitly get kicked out of the Ekumen because of his activities. The Ekumen remains very hands off, it’s the agents who can’t help but become involved, at least in the novels. I’ve always been bothered by the woman in The Matter of Seggri who just lets her partner be killed and continues to defend the sexism on that planet. I suppose that’s the point of the story.

I love the journey the main character goes on in The Telling and how in the end she finds way to justify helping.

@6/Flicker: “Old Music does explicitly get kicked out of the Ekumen because of his activities.”

He does? I don’t remember that. Can you tell me in which of the stories it was mentioned?

I don’t know whether it holds up, but I felt the first three of Le Guin’s novels came much later in the timeline than the other works in the Hainish cycle, so the lack of mindspeech in any but Left Hand of Darkness, is less of an omission. LHoD would then be the problem work.

@8/sujean: I don’t think that there is a timeline, at least not intentional. Le Guin said that she stopped using mindspeech because she no longer believed in it.

I read LHoD as a teenager, and I remember feeling feeling quite uncomfortable with the unusual gender issues. I still loved the novel, an now in my fifties I decided to re-read it. Wow. It is so tense, tragic and delicate at the same time, I was deeply moved by it. One of the greatest novels of the 20th century.

That made me re-read The Disposessed, which was great as well. However, the real revelation were the first three Hainian novels, especially City of Illusions. (Minor spoiler alert!) When Le Guin describes how lies and conspiracy theories divide population of the Earth into two very different segments, one couldn’t help thinking about the current political climate. If you really believe the others are the enemy, sooner or later they will become the enemy. And in the future city of Es Toch (somewhere in the Rockies?) sustaining that lie had become very advantageous for both sides. City of Illusions was very impressive, made me think.

“They seeded a code that “directed your evolution toward a physical form resembling ours”, as the alien message explains to the characters in the episode. That’s the best explanation for the abundance of hominids in science fiction I’ve seen so far”

Not a good explanation IMO; Earth’s evolution has shown no general drive toward hominid lifeforms, it’s just one branch of mammals. Especially when the seeding is said to have happened 4.5 billion years ago.

Better explanations are various “disapora from Earth” scenarios, involving an elder race, time travel, or a slow first colonization wave followed by later faster travel. Granted these tend to give you actual humans, not just ‘hominids’, but they could speciate if an author wanted.

Singularity Sky, Tom Paine Maru, Cosmonaut Keep, the Morgaine Cycle (though we never see space in that one), Stargate.

I headcanon that Niven’s Pak were engineered from Earth by a tnuctipun coming of stasis. There was a mission back to Earth from Pakworld, but that’s not where humans come from.